Design Part I: The Prequel

When we invent a garden we instinctively employ design principles. There is science, art and creativity in it. We will explore these in the three articles which will follow this one. But in this prequel we will discuss informally the manner in which we might approach a new garden. The type of garden doesn't much matter as the basic design tenets are generally universally applicable.

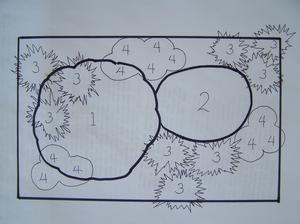

Imagine a potential new garden space on a flat plane. If easier to grasp then draw a rectangle on paper - the view from above, top/down. Our new garden will be wider than deep. We will make this an "island" garden, one that can be seen from all sides. Though we may soften the strict lines to gentle curves eventually for this exercise we will use the rectangle. This is an impressionistic sketch; we are neither going to impose exact specifics of size upon this garden nor of the specific heights and widths of the plants. All the plants are two-dimensional black and white renderings, mere suggestions of actual trees and shrubs as this exercise is just a basic, fundamental conceptualization.

Our tree (1) will be the anchor in this new garden. In contrast to herbaceous plants which die to the ground when temperatures plummet our specimen tree will, as with all woody plants, provide four seasons of structure. Woody plants in any garden may be thought of as the skeleton, the framework. Your chosen tree, the focal point, is the largest bone. Let's, for the sake of working together, place this chosen tree on the left of this garden about one-third the way in leaving about two thirds of empty space to the right of it.

Now let's choose a specimen shrub as a step down from our anchor (2). This woody shrub, smaller than the tree is nevertheless the second largest structural bone of the garden. It may be rounded or upright and vase-shaped in form but must not grow larger than our anchor, the tree. Let's place this plant just right of center slightly towards the backside of the garden.

Our next addition will be three groupings of one kind of shrub (3). These, nine in total, will be shorter growing than (2). These smaller shrubs will step down to the previous already set larger woody plants providing more height differential and another visual tier. With these three groupings we have even greater counterpoint and seasonal interest. Also, because of the use of repetition these bind and pull this garden together into a cohesive whole.

Our final addition to our skeletal outline will be another even smaller repeated shrub (4), eleven in total in three groups. Again, this repetition binds and pulls the garden together. This shrub will provide yet more counterpoint and four season interest. These basic bones provide tension and contrast. They provide dynamic height and size differences.

Now, with this very basic garden plan we can now begin to consider which woody plants might be possible. Will this garden be in full sun or shade? What is the soil texture and moisture retention like? In the given exposure we can then begin to consider culturally correct plant choices with thought to seasonal interest. Consider what these woody plants will look like in winter. If they are handsome in winter in terms of bark, berry and branching and if they contrast well with each other then they will be beautiful in all seasons. Switch in and out various possibilities always with consideration towards seasonal contrasts: bark texture and color, foliage texture and color in spring, summer and autumn. When do they flowers? Is there overlap to flowering times? Are there fall and winter berries, interesting seed heads? Do I want to feed the birds? Do I want a butterfly garden? This can be great satisfying fun.

When you've settled upon your woody plant skeleton flesh it out with clustered groups of appropriate perennials, ground covers, bulbs and/or annuals populating and completing the floor of the garden. Do this also with thought to some repetition for cohesion You may add a vine or two that will perhaps climb the tree (1) and/or scramble over the largest shrub (2).

The next 3 articles will be more daunting. But for those who challenge themselves these articles filled with definition may help you incorporate with greater understanding design principles, some which you may identify as presently and intuitively applying in your gardens. These articles may aid us in becoming more accomplished gardeners than we already are. Good as we are as there is always room for improvement. Get out those shovels or pencils. Dig into the soil or draw a design on paper. Clip these articles. Save them. Create. Invent. Consider them over the long winter. Have fun.

Penned by Wayne Paquette, January 2012